The 77-year-old Indigenous actor kept forgetting his lines. The director said three words that changed everything: “Tell your story.” What happened next made film history.

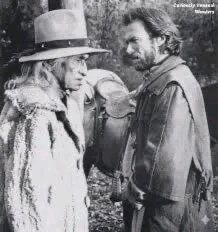

1976 Filming for “The Outlaw Josey Wales.”

Chief Dan George, the legendary Indigenous actor who’d made history six years earlier as the first Native American nominated for an Academy Award, was struggling.

At 77, memorizing pages of dialogue wasn’t as easy as it once was. Takes were running long. The script wasn’t flowing naturally.

Director Clint Eastwood watched, considered, then made a decision that would define some of cinema’s most powerful moments.

“Forget the exact words,” he told George. “Just tell me the story the way you’d tell it.”

It was more than just practical direction. It was an act of profound respect.

Chief Dan George was born Geswanouth Slahoot in 1899 on the Burrard Reserve in North Vancouver. For most of his life, he wasn’t an actor—he was a longshoreman, a father, and in 1951, became chief of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation.

He didn’t start acting until his 60s.

But when he did, he brought something Hollywood had never seen: authentic Indigenous voice, real authority, lived experience spanning nearly a century of change.

His breakthrough came in 1970 with “Little Big Man,” playing Old Lodge Skins opposite Dustin Hoffman. George rewrote some of his own dialogue to reflect actual Indigenous perspectives rather than Hollywood’s imagined version.

The performance earned him an Oscar nomination—the first Indigenous actor ever recognized by the Academy.

Hollywood noticed. Not just his talent, but what he represented: the possibility of Indigenous characters portrayed with full humanity rather than stereotypes.

When “The Outlaw Josey Wales” was being cast, George was the clear choice for Lone Watie—a Cherokee survivor of the Trail of Tears who becomes companion to Clint Eastwood’s outlaw protagonist.

The role was substantial. Lone Watie wasn’t comic relief or mystical guide. He was a fully realized character who’d lost everything to American expansion, finding unexpected family among fellow outcasts.

But age and the demands of memorization were creating challenges on set.

This is where many directors would have demanded retakes, used cue cards, or quietly started recasting conversations.

Eastwood, himself a longtime actor who understood performance from the inside, recognized something more valuable than perfect script adherence.

Chief Dan George carried the actual history of his people. When Lone Watie talked about the Trail of Tears, George wasn’t channeling research—he was speaking from generational memory, from stories passed down, from the lived reality of Indigenous survival.

So Eastwood gave him space to find his own path through scenes. To use his natural storytelling cadence rather than Hollywood’s written rhythms. To draw on his real voice rather than a screenwriter’s approximation.

The result transformed the film.

When George speaks about loss, about survival, about finding humor in tragedy, you hear authentic Indigenous storytelling. The phrasing reflects oral traditions, not screenplay formulas. The quiet dignity comes from someone who’s told these stories many times because they matter.

The relationship between Josey Wales and Lone Watie became the film’s emotional core—two men scarred by violence finding companionship in shared loss.

Roger Ebert called it “one of the best Westerns ever made.” It earned over $31 million and has endured as a genre landmark.

Chief Dan George’s performance is consistently cited as one of the film’s greatest strengths—a fully dimensional character bringing humor, wisdom, and heartbreaking humanity to every scene.

But George’s significance extended far beyond any single role.

For him, acting was advocacy. Every performance was an opportunity to present Indigenous people as fully human to audiences fed decades of dehumanizing stereotypes. To insist on dignity.